LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4IDI1cHggMHB4IDI1cHg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0gPiAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVyIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMjAwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9Ijk0MWY3MWY2YWY1MDk0MjNmMzlkMGE1M2RlNjg0MzE2Il0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogNDVweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAtMTAwcHg7Ym94LXNoYWRvdzogMXB4IC0xcHggMTBweCAwIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDAuNSApO21pbi1oZWlnaHQ6IDYwMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSIzZmNkODI0ZGMxNzQ0ZjY3NGJhYTExOWUzMGI2ZWUyNSJdIHsgYmFja2dyb3VuZDogcmdiYSggOTMsIDE3MywgMTk2LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzM1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjY2NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMSApO21hcmdpbi10b3A6IDQwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSBwIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxNnB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiA0MHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJlZDM4MzJhYTYyMDFjYmVjNWIxZTViOTAyZGMwNjdlMiJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9ImU3NmFkMWRiZWY2ZTEzNmJjZDcyMGIxYTM1ZjFlZGIzIl0gIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyMHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTVweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iNzRkZWZlMmM0NDRlMWEwMWQ1MjY2YjJiMjZjZmVkZDMiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuODA1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjE5NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjZlMDhkMWY2ZDNjYzgxNzQzYmRkMDZjYjhmOGNiZTNiIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXRvcDogMjVweDtkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSI3NmI5ZTE5YWViZDc4YjQ2N2IwNGM2NGFjZmUzMzE2NyJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMHB4OyB9IGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI0YzllYTlkNDYyZGI0MWZhOThhYzNjN2U1MTNhYjhmNiJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJjOWZhZDk4NmFmMGQ0M2IwNTFhN2EzZGNlYWQyNjk0MSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMThweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOiBjZW50ZXI7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iM2RhYWViMzdjMGZmYjA3MDVjNGViMWVkNTBlOGQ5MzUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMTRlYjU5OGM0NTczOTM2YzYxZDQ0MTU5ZDVlZWE0NDIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iMDVjNzEyYTVhMjJiNTlkZjFiZTRkMjg0ODcwNWQzMzUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDI0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDQwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDM0LCA4NCwgMTE4LCAxICk7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9ImEyMWI5OTg4MDg3MjNjOGFiMzU4MWNkMzIwM2ZiYmUzIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAwLCAwLCAwLCAwLjMyICkscmdiYSggMCwgMCwgMCwgMC4zMiApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDAgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciBjZW50ZXIgbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4O21hcmdpbi10b3A6IC01MDBweDttaW4taGVpZ2h0OiA1MDBweDtkaXNwbGF5Om1zLWZsZXhib3ggIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXggIWltcG9ydGFudDstbXMtZmxleC1kaXJlY3Rpb246Y29sdW1uO2ZsZXgtZGlyZWN0aW9uOmNvbHVtbjstbXMtZmxleC1wYWNrOmNlbnRlcjtqdXN0aWZ5LWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyOyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdID4gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lciB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTIwMHB4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdIHAgeyBsZXR0ZXItc3BhY2luZzogMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9ImVkMzgwMWMyMjk1ZDQ1N2E0MTg3NzdjMzgyNGRmMWIzIl0geyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSJlZDM4MDFjMjI5NWQ0NTdhNDE4Nzc3YzM4MjRkZjFiMyJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSBoMS50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iNzgyZDFmYThiODY3Y2VlM2UyNjk3ODE3ZTE4NzJhZGEiXSAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDY0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDUycHg7bGV0dGVyLXNwYWNpbmc6IDBweDt0ZXh0LXRyYW5zZm9ybTogdXBwZXJjYXNlO2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyO3BhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAwcHg7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206IDBweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiA3NXB4O21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206IDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjM2NjdlNzYzMWM0MjhjNzA0YjI5NjdiZGJhNzAxYTJiIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAwICkscmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMCApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDEgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciB0b3Agbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAwcHg7bWFyZ2luOiAwcHg7bWluLWhlaWdodDogNTAwcHg7IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iOTQxZjcxZjZhZjUwOTQyM2YzOWQwYTUzZGU2ODQzMTYiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmctcmlnaHQ6IDE1cHg7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OiAxNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyNHB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAzMnB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9IjA1YzcxMmE1YTIyYjU5ZGYxYmU0ZDI4NDg3MDVkMzM1Il0gcCB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogMzJweDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfWgxLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI3ODJkMWZhOGI4NjdjZWUzZTI2OTc4MTdlMTg3MmFkYSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogNDhweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gfSA=

A groundbreaking SCRIPPS Institution of Oceanography voyage led by students helps define a rising environmental threat.

LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4IDI1cHggMHB4IDI1cHg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0gPiAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVyIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMjAwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9Ijk0MWY3MWY2YWY1MDk0MjNmMzlkMGE1M2RlNjg0MzE2Il0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogNDVweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAtMTAwcHg7Ym94LXNoYWRvdzogMXB4IC0xcHggMTBweCAwIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDAuNSApO21pbi1oZWlnaHQ6IDYwMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSIzZmNkODI0ZGMxNzQ0ZjY3NGJhYTExOWUzMGI2ZWUyNSJdIHsgYmFja2dyb3VuZDogcmdiYSggOTMsIDE3MywgMTk2LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzM1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjY2NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMSApO21hcmdpbi10b3A6IDQwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSBwIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxNnB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiA0MHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJlZDM4MzJhYTYyMDFjYmVjNWIxZTViOTAyZGMwNjdlMiJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9ImU3NmFkMWRiZWY2ZTEzNmJjZDcyMGIxYTM1ZjFlZGIzIl0gIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyMHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTVweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iNzRkZWZlMmM0NDRlMWEwMWQ1MjY2YjJiMjZjZmVkZDMiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuODA1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjE5NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjZlMDhkMWY2ZDNjYzgxNzQzYmRkMDZjYjhmOGNiZTNiIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXRvcDogMjVweDtkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSI3NmI5ZTE5YWViZDc4YjQ2N2IwNGM2NGFjZmUzMzE2NyJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMHB4OyB9IGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI0YzllYTlkNDYyZGI0MWZhOThhYzNjN2U1MTNhYjhmNiJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJjOWZhZDk4NmFmMGQ0M2IwNTFhN2EzZGNlYWQyNjk0MSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMThweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOiBjZW50ZXI7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iM2RhYWViMzdjMGZmYjA3MDVjNGViMWVkNTBlOGQ5MzUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMTRlYjU5OGM0NTczOTM2YzYxZDQ0MTU5ZDVlZWE0NDIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iMDVjNzEyYTVhMjJiNTlkZjFiZTRkMjg0ODcwNWQzMzUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDI0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDQwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDM0LCA4NCwgMTE4LCAxICk7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9ImEyMWI5OTg4MDg3MjNjOGFiMzU4MWNkMzIwM2ZiYmUzIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAwLCAwLCAwLCAwLjMyICkscmdiYSggMCwgMCwgMCwgMC4zMiApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDAgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciBjZW50ZXIgbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4O21hcmdpbi10b3A6IC01MDBweDttaW4taGVpZ2h0OiA1MDBweDtkaXNwbGF5Om1zLWZsZXhib3ggIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXggIWltcG9ydGFudDstbXMtZmxleC1kaXJlY3Rpb246Y29sdW1uO2ZsZXgtZGlyZWN0aW9uOmNvbHVtbjstbXMtZmxleC1wYWNrOmNlbnRlcjtqdXN0aWZ5LWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyOyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdID4gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lciB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTIwMHB4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdIHAgeyBsZXR0ZXItc3BhY2luZzogMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9ImVkMzgwMWMyMjk1ZDQ1N2E0MTg3NzdjMzgyNGRmMWIzIl0geyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSJlZDM4MDFjMjI5NWQ0NTdhNDE4Nzc3YzM4MjRkZjFiMyJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSBoMS50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iNzgyZDFmYThiODY3Y2VlM2UyNjk3ODE3ZTE4NzJhZGEiXSAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDY0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDUycHg7bGV0dGVyLXNwYWNpbmc6IDBweDt0ZXh0LXRyYW5zZm9ybTogdXBwZXJjYXNlO2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyO3BhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAwcHg7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206IDBweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiA3NXB4O21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206IDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjM2NjdlNzYzMWM0MjhjNzA0YjI5NjdiZGJhNzAxYTJiIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAwICkscmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMCApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDEgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciB0b3Agbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAwcHg7bWFyZ2luOiAwcHg7bWluLWhlaWdodDogNTAwcHg7IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iOTQxZjcxZjZhZjUwOTQyM2YzOWQwYTUzZGU2ODQzMTYiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmctcmlnaHQ6IDE1cHg7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OiAxNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyNHB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAzMnB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9IjA1YzcxMmE1YTIyYjU5ZGYxYmU0ZDI4NDg3MDVkMzM1Il0gcCB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogMzJweDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfWgxLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI3ODJkMWZhOGI4NjdjZWUzZTI2OTc4MTdlMTg3MmFkYSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogNDhweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gfSA=

Last summer, minutes before leaving port on a voyage to the North Pacific Ocean Gyre, Chief Scientist Miriam Goldstein was frank about what might and might not be encountered during the expedition to a place that’s become known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” Goldstein made it clear to fellow scientists, cruise volunteers, and a few members of the news media that SEAPLEX would be an exploratory voyage.

The expedition was designed to locate and study plastic and other marine debris in the gyre. But finding the stuff wasn’t guaranteed. In some ways, the voyage would pay tribute to the grand oceanographic exploration days of yesteryear when seagoing scientists plunged into the great unknown of the ocean frontier. SEAPLEX (Scripps Environmental Accumulation of Plastic Expedition) was designed to learn something about the scope of the debris problem. It’s quite possible, Goldstein said, that the graduate student researchers leading the trip – despite diligent preparations and knowledge gained from previous trips headed by the Algalita Marine Research Foundation – might not find any plastic in the gyre.

But less than a week into the voyage such provisos evaporated into wisps of sea air. The plastic indeed was there in the gyre. And there was lots and lots of it. Way out here in the open ocean, a thousand miles from land, the plastic was all around the boat. Litters of small flecks were here. A floating bucket and a piece of shoe there.

Today, the graduate student researchers are well into the analysis phase of their science. Now that the plastic has been found and documented, they are hoping the SEAPLEX journey will reveal answers to questions such as how the plastic is impacting the gyre’s marine ecosystems and animals. The information would provide key information about human-produced marine pollution and how to grapple with a rising environmental problem that could be turning all of the ocean’s gyres into trash dumps.

Plastic in a Biological Desert

SEAPLEX scientists called the North Pacific Gyre a “biological desert,” an area with marine life, to be sure, but devoid of robust, productive ecosystems seen elsewhere. The gyre exists as a consequence of the earth’s rotation called the Coriolis Force that pushes wind in a clockwise circle around the North Pacific Ocean. The force, also responsible for gyres in the South Pacific as well as the planet’s other oceans, causes water to collect in the middle of the wind, creating a vortex known as a “convergence zone.” Gentle winds and circulation make the gyre a place most seafarers avoid and its remoteness has made it an understudied location.

“As the wind moves new water into the middle of the convergence zone, the water that was there before sinks,” Scripps graduate student and SEAPLEX voyager Pete Davison explained. “The sinking water leaves floating material behind. New plastic comes in and the old plastic stays behind.”

Trash Talking

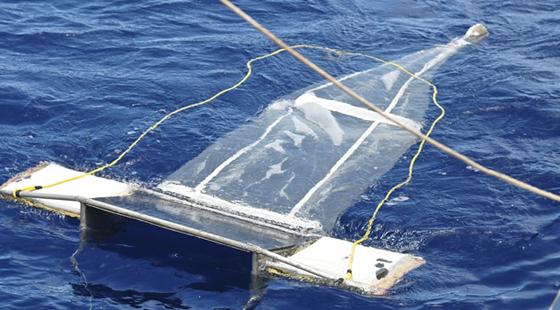

A Manta Net

Scientists deploy manta nets, named because of a shape that resembles a manta ray, to collect small specimens and objects from the sea surface. By the early morning hours of the next day, the manta net would be the first of the expedition’s four main collection tools to retrieve plastic samples. In the end, it collected plastic samples in every haul, for more than 100 consecutive tows across a distance of more than 2,375 kilometers (1,700 miles).

During the survey in the inflatable boat, Goldstein used a quadrat, a frame that defines an area of a habitat, to gauge the quantity of plastic in a given area. At maximum, she detected 11 pieces per square meter.

“That’s a lot of anything to be out in the open ocean,” said Goldstein. “The thing I found sad and shocking was that we could see some amazing, cool creatures just below this thick layer of plastic. Here’s this very unstudied ecosystem where not many people come and there is all this stuff floating at the top that’s a sign of industrial society.”

The Garbage Patch Kids

As New Horizon began steaming back to port, the researchers discussed the lessons learned from the voyage, especially facts countering public myths about the Garbage Patch. The “patch” isn’t an island of trash, as is commonly believed. You can’t walk across it. There is indeed a vast amount of large pieces of debris, but by far the overwhelming majority is broken down bits of plastic the size of a thumbnail and smaller. You can’t see a defined patch or a swirl of debris from the air or space. The plastic is dispersed across thousands of miles of ocean.

Hundreds of samples and specimens from SEAPLEX are being analyzed and results are on the horizon. For Davison, the “fish guy” on the science team, the specimens have already yielded tantalizing returns. He and fellow Scripps graduate student Rebecca Asch have dissected the stomachs of more than a hundred specimens. In their Scripps laboratory, they have used a stain and filtering process to segregate biological from human-made substances and found direct evidence that deep-sea gyre fish such as lanternfish are ingesting bits of plastic. Even a low percentage of plastic ingestion is raising troubling questions about how garbage can work its way through the marine food chain. “The pollutants are potentially harmful to the fish,” Davison said. “We don’t eat these fish directly, but fish that we do eat feed on them so plastic entering the food chain may be a concern to people.”

Chelsea Rochman, a San Diego State University and UC Davis graduate student, is analyzing the toxicological aspects of plastic ingestion by animals in the gyre, specifically how plastics might be a transport medium for toxins such as the industrial chemical BPA (bisphenol A) to enter the food web, with possible future implications for human health.

Goldstein is probing the impact of plastic debris on marine invertebrates. Students Darcy Taniguchi and Meg Rippy are analyzing water samples taken during the cruise to investigate the influence of debris on bacteria and phytoplankton. Through SEAPLEX, the scientists have set a baseline that will inform future missions targeting the North Pacific Gyre, and possibly other ocean gyres in the future.

Barnacles and mussels hitch on to plastic debris.

Doug Woodring is a business executive, environmentalist, and co-founder of Project Kaisei, which supported part of the SEAPLEX expedition along with UC Ship Funds. He used the expedition as a springboard to begin to formulate solutions to the plastics problem on different fronts. At sea, he and his partners are evaluating new remediation technologies and techniques to capture debris. On land, he is discussing solutions with multinational industry representatives to encourage new packaging – specifically biodegradable materials – in an effort to stop the garbage problem before it ever reaches the sea.

“Like most people, I expected to see large volumes of big material en masse in the gyre. I now realize that the sun plays a big role in breaking down material, which then degrades and scatters,” said Woodring. Despite gains in recent years, Woodring says that approximately 90 percent of all consumer materials are not recycled. When SEAPLEX’s scientific findings emerge, he hopes they will force societies into thinking about the plastic surrounding them.

“It’s tragic that (the ocean debris problem) has been allowed to happen, and it happened in the last 40 or 50 years,” said Woodring. “A lot of plastic is permanent material for disposable uses. This should be a wake up call to all of us that we need something more environmentally friendly.”