LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4IDI1cHggMHB4IDI1cHg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0gPiAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVyIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMjAwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9Ijk0MWY3MWY2YWY1MDk0MjNmMzlkMGE1M2RlNjg0MzE2Il0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogNDVweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAtMTAwcHg7Ym94LXNoYWRvdzogMXB4IC0xcHggMTBweCAwIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDAuNSApO21pbi1oZWlnaHQ6IDYwMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSIzZmNkODI0ZGMxNzQ0ZjY3NGJhYTExOWUzMGI2ZWUyNSJdIHsgYmFja2dyb3VuZDogcmdiYSggOTMsIDE3MywgMTk2LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzM1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjY2NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMSApO21hcmdpbi10b3A6IDQwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSBwIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxNnB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiA0MHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJlZDM4MzJhYTYyMDFjYmVjNWIxZTViOTAyZGMwNjdlMiJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9ImU3NmFkMWRiZWY2ZTEzNmJjZDcyMGIxYTM1ZjFlZGIzIl0gIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyMHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTVweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iNzRkZWZlMmM0NDRlMWEwMWQ1MjY2YjJiMjZjZmVkZDMiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuODA1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjE5NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjZlMDhkMWY2ZDNjYzgxNzQzYmRkMDZjYjhmOGNiZTNiIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXRvcDogMjVweDtkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSI3NmI5ZTE5YWViZDc4YjQ2N2IwNGM2NGFjZmUzMzE2NyJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMHB4OyB9IGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI0YzllYTlkNDYyZGI0MWZhOThhYzNjN2U1MTNhYjhmNiJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJjOWZhZDk4NmFmMGQ0M2IwNTFhN2EzZGNlYWQyNjk0MSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMThweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOiBjZW50ZXI7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iM2RhYWViMzdjMGZmYjA3MDVjNGViMWVkNTBlOGQ5MzUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMTRlYjU5OGM0NTczOTM2YzYxZDQ0MTU5ZDVlZWE0NDIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iMDVjNzEyYTVhMjJiNTlkZjFiZTRkMjg0ODcwNWQzMzUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDI0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDQwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDM0LCA4NCwgMTE4LCAxICk7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9ImEyMWI5OTg4MDg3MjNjOGFiMzU4MWNkMzIwM2ZiYmUzIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAwLCAwLCAwLCAwLjMyICkscmdiYSggMCwgMCwgMCwgMC4zMiApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDAgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciBjZW50ZXIgbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4O21hcmdpbi10b3A6IC01MDBweDttaW4taGVpZ2h0OiA1MDBweDtkaXNwbGF5Om1zLWZsZXhib3ggIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXggIWltcG9ydGFudDstbXMtZmxleC1kaXJlY3Rpb246Y29sdW1uO2ZsZXgtZGlyZWN0aW9uOmNvbHVtbjstbXMtZmxleC1wYWNrOmNlbnRlcjtqdXN0aWZ5LWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyOyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdID4gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lciB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTIwMHB4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdIHAgeyBsZXR0ZXItc3BhY2luZzogMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9ImVkMzgwMWMyMjk1ZDQ1N2E0MTg3NzdjMzgyNGRmMWIzIl0geyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSJlZDM4MDFjMjI5NWQ0NTdhNDE4Nzc3YzM4MjRkZjFiMyJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSBoMS50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iNzgyZDFmYThiODY3Y2VlM2UyNjk3ODE3ZTE4NzJhZGEiXSAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDY0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDUycHg7bGV0dGVyLXNwYWNpbmc6IDBweDt0ZXh0LXRyYW5zZm9ybTogdXBwZXJjYXNlO2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyO3BhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAwcHg7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206IDBweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiA3NXB4O21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206IDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjM2NjdlNzYzMWM0MjhjNzA0YjI5NjdiZGJhNzAxYTJiIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAwICkscmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMCApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDEgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciB0b3Agbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAwcHg7bWFyZ2luOiAwcHg7bWluLWhlaWdodDogNTAwcHg7IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iOTQxZjcxZjZhZjUwOTQyM2YzOWQwYTUzZGU2ODQzMTYiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmctcmlnaHQ6IDE1cHg7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OiAxNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyNHB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAzMnB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9IjA1YzcxMmE1YTIyYjU5ZGYxYmU0ZDI4NDg3MDVkMzM1Il0gcCB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogMzJweDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfWgxLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI3ODJkMWZhOGI4NjdjZWUzZTI2OTc4MTdlMTg3MmFkYSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogNDhweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gfSA=

The commercial fishing boats plying the waters of Alaska’s Bristol Bay were once wooden sailboats. Boatyards built these double-enders of Port Orford cedar planking with stout ribs of white oak. From these 30-foot vessels, fishermen pulled their nets by hand and in this way they caught millions of wild salmon each year. Fishing in these boats was “not a push-button experience,” as one fishermen’s daughter put it.

LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4IDI1cHggMHB4IDI1cHg7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjUwZWUyMTY1MTllYzRkYWJkNWZkNmIwMGQ2N2Y4MWRmIl0gPiAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVyIHsgbWF4LXdpZHRoOiAxMjAwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9Ijk0MWY3MWY2YWY1MDk0MjNmMzlkMGE1M2RlNjg0MzE2Il0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogNDVweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiAtMTAwcHg7Ym94LXNoYWRvdzogMXB4IC0xcHggMTBweCAwIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDAuNSApO21pbi1oZWlnaHQ6IDYwMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSIzZmNkODI0ZGMxNzQ0ZjY3NGJhYTExOWUzMGI2ZWUyNSJdIHsgYmFja2dyb3VuZDogcmdiYSggOTMsIDE3MywgMTk2LCAxICk7cGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuMzM1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjY2NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMSApO21hcmdpbi10b3A6IDQwcHg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iNDY3MDMzZjZmOWI1YTMwZDdhMGJlYzdjYjJiMzgyYTUiXSBwIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAxNnB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiA0MHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjMwMzRmYmU4ODZjMTEwNTRlOTViNDZiMDlkM2U0MTEyIl0geyBkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJlZDM4MzJhYTYyMDFjYmVjNWIxZTViOTAyZGMwNjdlMiJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMjVweDsgfSAudGItaGVhZGluZ1tkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWhlYWRpbmc9ImU3NmFkMWRiZWY2ZTEzNmJjZDcyMGIxYTM1ZjFlZGIzIl0gIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyMHB4O2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTVweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iNzRkZWZlMmM0NDRlMWEwMWQ1MjY2YjJiMjZjZmVkZDMiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuODA1ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjE5NWZyKTtncmlkLWF1dG8tZmxvdzogcm93IH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAxKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAxIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0gPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMm4gKyAyKSB7IGdyaWQtY29sdW1uOiAyIH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW49IjZlMDhkMWY2ZDNjYzgxNzQzYmRkMDZjYjhmOGNiZTNiIl0geyBwYWRkaW5nLXRvcDogMjVweDtkaXNwbGF5OiBmbGV4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSI3NmI5ZTE5YWViZDc4YjQ2N2IwNGM2NGFjZmUzMzE2NyJdIHsgcGFkZGluZzogMHB4OyB9IGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI0YzllYTlkNDYyZGI0MWZhOThhYzNjN2U1MTNhYjhmNiJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMTZweDt0ZXh0LWRlY29yYXRpb246IG5vbmU7IH0gIGgyLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSJjOWZhZDk4NmFmMGQ0M2IwNTFhN2EzZGNlYWQyNjk0MSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMThweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOiBjZW50ZXI7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDogMTBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iM2RhYWViMzdjMGZmYjA3MDVjNGViMWVkNTBlOGQ5MzUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMTRlYjU5OGM0NTczOTM2YzYxZDQ0MTU5ZDVlZWE0NDIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWZpZWxkcy1hbmQtdGV4dD0iMDVjNzEyYTVhMjJiNTlkZjFiZTRkMjg0ODcwNWQzMzUiXSB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDtjb2xvcjogcmdiYSggMzQsIDg0LCAxMTgsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDI0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDQwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDM0LCA4NCwgMTE4LCAxICk7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9ImEyMWI5OTg4MDg3MjNjOGFiMzU4MWNkMzIwM2ZiYmUzIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAwLCAwLCAwLCAwLjMyICkscmdiYSggMCwgMCwgMCwgMC4zMiApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDAgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciBjZW50ZXIgbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAyNXB4O21hcmdpbi10b3A6IC01MDBweDttaW4taGVpZ2h0OiA1MDBweDtkaXNwbGF5Om1zLWZsZXhib3ggIWltcG9ydGFudDtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXggIWltcG9ydGFudDstbXMtZmxleC1kaXJlY3Rpb246Y29sdW1uO2ZsZXgtZGlyZWN0aW9uOmNvbHVtbjstbXMtZmxleC1wYWNrOmNlbnRlcjtqdXN0aWZ5LWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyOyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdID4gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lciB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTIwMHB4OyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXIudGItY29udGFpbmVyW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyPSJhMjFiOTk4ODA4NzIzYzhhYjM1ODFjZDMyMDNmYmJlMyJdIHAgeyBsZXR0ZXItc3BhY2luZzogMHB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9ImVkMzgwMWMyMjk1ZDQ1N2E0MTg3NzdjMzgyNGRmMWIzIl0geyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSJlZDM4MDFjMjI5NWQ0NTdhNDE4Nzc3YzM4MjRkZjFiMyJdIHAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDIwcHg7Y29sb3I6IHJnYmEoIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAyNTUsIDEgKTsgfSBoMS50Yi1oZWFkaW5nW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtaGVhZGluZz0iNzgyZDFmYThiODY3Y2VlM2UyNjk3ODE3ZTE4NzJhZGEiXSAgeyBmb250LXNpemU6IDY0cHg7bGluZS1oZWlnaHQ6IDUycHg7bGV0dGVyLXNwYWNpbmc6IDBweDt0ZXh0LXRyYW5zZm9ybTogdXBwZXJjYXNlO2NvbG9yOiByZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAxICk7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjogY2VudGVyO3BhZGRpbmctdG9wOiAwcHg7cGFkZGluZy1ib3R0b206IDBweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOiA3NXB4O21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206IDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lci50Yi1jb250YWluZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1jb250YWluZXI9IjM2NjdlNzYzMWM0MjhjNzA0YjI5NjdiZGJhNzAxYTJiIl0geyBiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOmxpbmVhci1ncmFkaWVudChyZ2JhKCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMjU1LCAwICkscmdiYSggMjU1LCAyNTUsIDI1NSwgMCApKSwgIHJnYmEoIDAsIDAsIDAsIDEgKSB1cmwoJycpIGNlbnRlciB0b3Agbm8tcmVwZWF0O2JhY2tncm91bmQtc2l6ZTphdXRvLCBjb3ZlcjtwYWRkaW5nOiAwcHg7bWFyZ2luOiAwcHg7bWluLWhlaWdodDogNTAwcHg7IH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfS50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSB7IGdyaWQtdGVtcGxhdGUtY29sdW1uczogbWlubWF4KDAsIDAuNWZyKSBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDEpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDEgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSA+IC50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbjpudGgtb2YtdHlwZSgybiArIDIpIHsgZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46IDIgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW5bZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj0iMzAzNGZiZTg4NmMxMTA1NGU5NWI0NmIwOWQzZTQxMTIiXSB7IGRpc3BsYXk6IGZsZXg7IH0gLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS50Yi1ncmlkLC50Yi1ncmlkPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItaW5uZXItYmxvY2tzPi5ibG9jay1lZGl0b3ItYmxvY2stbGlzdF9fbGF5b3V0e2Rpc3BsYXk6Z3JpZDtncmlkLXJvdy1nYXA6MjVweDtncmlkLWNvbHVtbi1nYXA6MjVweH0udGItZ3JpZC1pdGVte2JhY2tncm91bmQ6I2QzOGEwMztwYWRkaW5nOjMwcHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1ue2ZsZXgtd3JhcDp3cmFwfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbj4qe3dpZHRoOjEwMCV9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tdG9we3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1zdGFydH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1jZW50ZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tYm90dG9te3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6ZmxleC1lbmR9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdIHsgZ3JpZC10ZW1wbGF0ZS1jb2x1bW5zOiBtaW5tYXgoMCwgMC41ZnIpIG1pbm1heCgwLCAwLjVmcik7Z3JpZC1hdXRvLWZsb3c6IHJvdyB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLnRiLWdyaWRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkPSI0YjU1YWRmMWQzMzFmNDk2ZjhhM2I3OWJjNTkwMDczMCJdID4gLnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uOm50aC1vZi10eXBlKDJuICsgMikgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMiB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30udGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtY29udGFpbmVyLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lcltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWNvbnRhaW5lcj0iOTQxZjcxZjZhZjUwOTQyM2YzOWQwYTUzZGU2ODQzMTYiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmctcmlnaHQ6IDE1cHg7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OiAxNXB4OyB9IC50Yi1jb250YWluZXIgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lci1pbm5lcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO21hcmdpbjowIGF1dG99LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjE0ZWM4YWNmYmM2NGFmODg4Njc4OTBkNzhhZjU2OGM5Il0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iMTRlYzhhY2ZiYzY0YWY4ODg2Nzg5MGQ3OGFmNTY4YzkiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIzMDM0ZmJlODg2YzExMDU0ZTk1YjQ2YjA5ZDNlNDExMiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gLndwLWJsb2NrLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQudGItZ3JpZFtkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQ9IjRiNTVhZGYxZDMzMWY0OTZmOGEzYjc5YmM1OTAwNzMwIl0geyBncmlkLXRlbXBsYXRlLWNvbHVtbnM6IG1pbm1heCgwLCAxZnIpO2dyaWQtYXV0by1mbG93OiByb3cgfSAud3AtYmxvY2stdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZC50Yi1ncmlkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZ3JpZD0iNGI1NWFkZjFkMzMxZjQ5NmY4YTNiNzliYzU5MDA3MzAiXSAgPiAudGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW46bnRoLW9mLXR5cGUoMW4rMSkgeyBncmlkLWNvbHVtbjogMSB9IC53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSI2ZTA4ZDFmNmQzY2M4MTc0M2JkZDA2Y2I4ZjhjYmUzYiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfS53cC1ibG9jay10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbltkYXRhLXRvb2xzZXQtYmxvY2tzLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPSIxNGViNTk4YzQ1NzM5MzZjNjFkNDQxNTlkNWVlYTQ0MiJdIHsgZGlzcGxheTogZmxleDsgfSAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIwNWM3MTJhNWEyMmI1OWRmMWJlNGQyODQ4NzA1ZDMzNSJdIHsgZm9udC1zaXplOiAyNHB4O2xpbmUtaGVpZ2h0OiAzMnB4OyB9IC50Yi1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZHMtYW5kLXRleHQ9IjA1YzcxMmE1YTIyYjU5ZGYxYmU0ZDI4NDg3MDVkMzM1Il0gcCB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogMjRweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogMzJweDsgfSAudGItY29udGFpbmVyIC50Yi1jb250YWluZXItaW5uZXJ7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTttYXJnaW46MCBhdXRvfWgxLnRiLWhlYWRpbmdbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1oZWFkaW5nPSI3ODJkMWZhOGI4NjdjZWUzZTI2OTc4MTdlMTg3MmFkYSJdICB7IGZvbnQtc2l6ZTogNDhweDtsaW5lLWhlaWdodDogNDBweDsgfSAgLnRiLWNvbnRhaW5lciAudGItY29udGFpbmVyLWlubmVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7bWFyZ2luOjAgYXV0b30gfSA=

Bristol Bay’s sailboat era hung on until the 1950s, and much changed in the ensuing decades. One thing has remained remarkably constant, however: the fish. Even now, the 128th year of commercial salmon fishing in Bristol Bay, this remains without question the greatest wild salmon run on Earth.

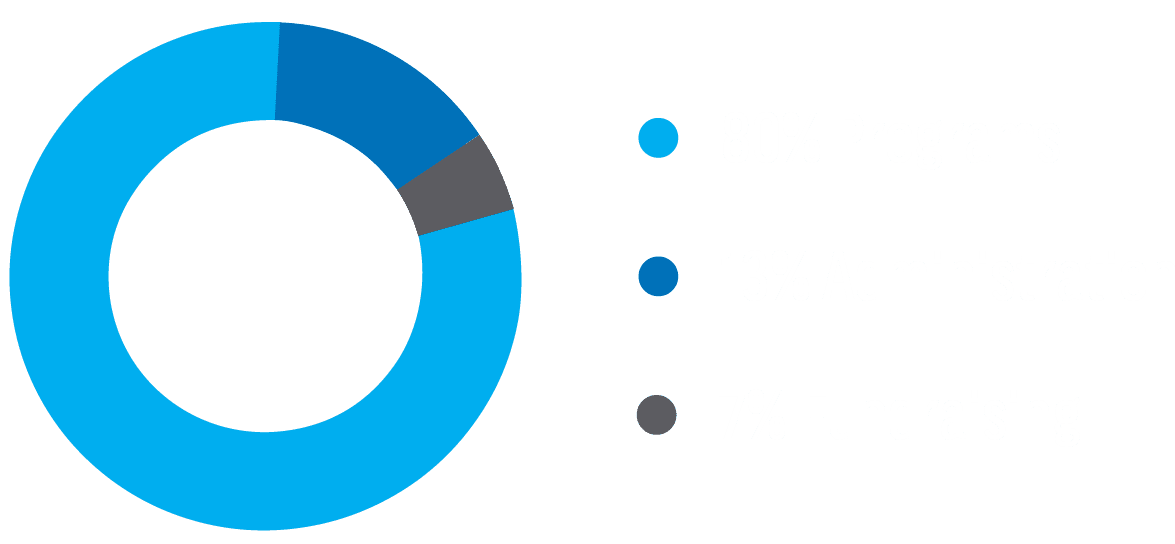

All five species of Pacific salmon occurring in North America migrate to the Bristol Bay headwaters each summer. Its giant freshwater lakes offer especially ideal habitat for spawning sockeye salmon, which return to their natal waters after 1-3 years at sea. The Bristol Bay watershed produces 51 percent of the wild sockeye salmon on the planet. Its two major rivers, the Kvichak River and Lake Iliamna system and the Nushagak River, alone produce one-fifth of the world’s wild sockeye salmon. Chances are good that the fresh filet of wild sockeye appearing on a plate anywhere in the world has come from Bristol Bay.

History of Sustainability

At a time when society is rightly questioning the sustainability of some of the world’s fisheries, the longevity of Bristol Bay’s fishing industry illustrates its solid track record. And like all Alaska salmon fisheries, its management is in accord with United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization standards. The Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch lists Alaska salmon as a “best choice.”

Over the last 20 years, the annual run has averaged 40 million wild sockeye. These returns bring substantial earnings to hundreds of small-operator fishermen and businesses. The fishery is valued at $480 million annually, but the natural phenomenon of the salmon migration, now and into the future, has a larger value.

As “King of Fish” author David Montgomery told the PBS Frontline program in a July 24, 2012 episode, it’s difficult to put an economic value on a salmon run that can be fished forever.

These salmon runs simultaneously support a healthy ecosystem: Eagles, bears, wolves, beluga whales, orca whales, sea otters, and even caddis flies – in all some 40 species – depend directly on the nutrient wealth that salmon deliver from the sea to the farthest reaches of the watershed. If you’ve ever watched footage of brown bears fishing for salmon, it was quite likely filmed in Bristol Bay.

Pristine Habitat

Why does this spectacular natural system still function in the year 2012? In short, the habitat is entirely intact. Reaching across a vast territory of mountains and tundra, lakes and wetlands in an area the size of Ohio, the Bristol Bay headwaters are nearly pristine. Some of the factors that contributed to the decline of salmon runs elsewhere – roads, dams, urbanization, agriculture – are nearly nonexistent here.

For these reasons, Bristol Bay remains a globally unique resource: a wild fishery that fuels a thriving industry while at the same time underpinning one of the wildest ecosystems on Earth. We know that if the wild salmon are abundant, the ecosystem will be healthy, and the region’s communities will be, too.

Conservation for People

The harvest of wild salmon lies at the heart of the local indigenous tradition. As Thomas Tilden, the chief of the Curyung Tribe, has said, “In my community, we sing, we dance, we do art – all around salmon. That is who we are.”

The archeological record shows people have harvested salmon from these waters for at least 7,000 years. Today, the tradition continues: families prepare their salmon catch in smokehouses, their stoves stoked with cottonwood. The value of this tradition is simply beyond measure. Lastly, the freshwater streams and lakes in the Bristol Bay headwaters are a world-class destination for fly-fishermen pursuing 10-pound-plus rainbow trout, chrome-bright coho salmon and 30-pound-plus Chinook salmon.

Looming Proposal to Mine Minerals

The Nature Conservancy began protecting fish and wildlife habitat here in the early 1990s, largely through the use of land purchases and conservation easements intended to prevent isolated pockets of development such as remote recreational subdivisions. Our approach to protecting habitat has become more comprehensive as the risks to salmon habitat have grown to include large-scale mining.

The largest mineral prospect in the region, the Pebble, is a gold and copper deposit located on 90 square miles of state-owned land about 25 miles north of Lake Iliamna. This area straddles the headwaters of the Nushagak and Kvichak rivers – the two most productive sockeye rivers on the planet. A mine proposal would likely include an open pit mine, or underground mine, or both, with an open pit measuring two square miles. Other project details could also include nine miles of tailings dams with a height reaching 740 feet, a newly developed deep-water port connected to the mine site by a 104-mile long road and pipeline, a 300-megawatt power plant and a 135-mile transmission line.

In recent years, the Conservancy has built a research program aimed at collecting the baseline data necessary for assessing the resource at risk from large-scale development. This work consists of a range of activities including community-based conservation, and scientific inventories of fish, hydrology, water quality and aquatic invertebrate communities. To better understand potential risks to salmon from potential large-scale mining, we commissioned an ecological risk assessment in 2007.

The Conservancy has added 120 miles of previously undocumented, and therefore unprotected, salmon streams to the state’s official inventory. In addition, the Conservancy is protecting stream flows for fish on seven critical streams and rivers. Tribes, local residents and businesses have asked the EPA to review development proposals and ultimately prohibit the disposal of mining wastes in the watershed, using its authority under the Clean Water Act. The agency’s assessment has confirmed that development in this region would result in the loss of wetlands and salmon streams. Water withdrawals would diminish the habitat value of some streams. Risks associated with large-scale mining projects – such as acid mine drainage or a breach in tailings dams – pose significant risks to salmon.

Salmon without End?

In Bristol Bay and across Alaska and the nation, the debate over the future of the planet’s most productive wild salmon ecosystem has brought much attention to this remote region.

Meanwhile, the salmon runs of Bristol Bay – and the traditions that depend on them – continue as they have for millennia. The people whose lives are inextricably linked to the future of the salmon are all too aware of a threat looming upstream.

Randall Hagenstein has an extensive background in natural resource issues with 25 years of experience in conservation, research, analysis, management, and use of natural resources, especially in northern ecosystems. Randall was a commercial salmon fisherman for several years, and his educational background includes a B.A. from Middlebury College in Northern Studies and a master’s degree from Yale University in forest ecology and silviculture. He lives with his family in Anchorage.